(name for this piece generously provided by Tim Hecker)

Sampling, the act of taking one piece of recorded music or sound and using it within the performance of another, has existed academically since the 1930s, and grew in profile when composers like Karlheinz Stockhausen and, um, John Lennon started doing it to make ambient sound collages by then referred to as musique concrete. But even though the idea made it on to a Beatles record, it didn’t really escape the avant-garde until the ‘90s when it found its political counterpart; situationally-minded hip hop artists, working towards the salvation and liberation of black American life, used sampling as a means of re-contextualizing and reclaiming any sort of aesthetic material they could, back from the racist culture they were rebelling against. It was an intersection of technique and philosophy that, as anyone reading this knows, thoroughly captured the American imagination and sparked as much debate about the nature of art itself from the aesthetically minded as it did the specifics of intellectual property law from cynical corporate lawyers.

Furthermore, sampling was integral in the creation of some incredibly innovative music: Public Enemy’s crude but effective blend of punk and politics, the absurd and detailed psychedelic tapestries of The Avalanches, Kanye’s prescient embrace of French techno in the mid aughts, well… I could go on, but you already know the story, ‘cause by now, it’s almost a cliché. Anyways, like most things, sampling got kinda weird in the last ten years, in ways that underscore not only the absurdity of late capitalism, but also the brain-drain in mainstream pop that has vanguard artists resorting to empty spectacle and shock tactics in the absence of music that can stand on its own two feet.

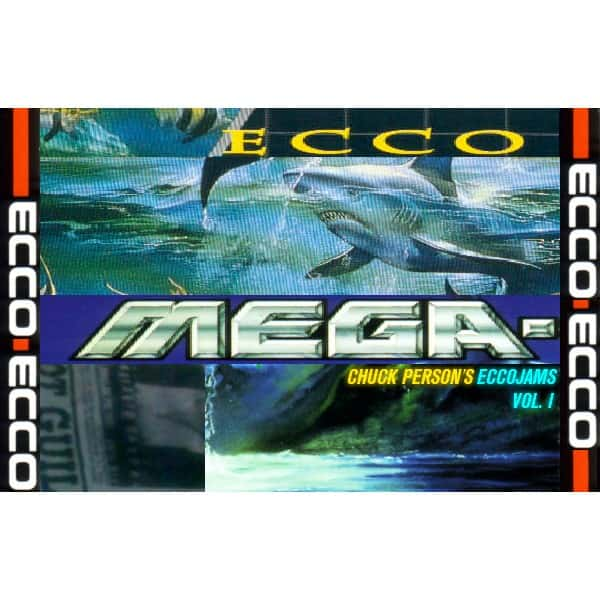

At the turn of the decade, sampling mutated into something even more internet-oriented and populist than it was at the dawn of hip-hop, first in the form of “Chuck Person’s” Ecco-Jams (or, as a genre, vaporwave). The brainchild of one of modern music’s most fascinating figures, Daniel Lopatin (AKA Oneohtrix Point Never), Ecco-Jams were conceived as folk songs for the modern world; after all, anyone with a computer can download a free digital audio workstation like Audacity, then use it to chop up, pitch down, and magically render beautiful and absurd the art works of the commonplace. And, for a brief moment in time, it really did seem like everyone was doing it: vaporwave labels and releases spread like a virus throughout the far reaches of the internet, bleeding into an already thoroughly online pop culture in ways that I’m confident you, dear reader, probably already have a pretty intuitive feel for. And because this is the 2010s we’re talking about, the basic idea of vaporwave continuously refracted through the cultural prism that is the internet, finding expression in the Derrida-inspired “hauntological” work of The Caretaker as well as hypnagogic pop or, um, chillwave, if you prefer.

Anyways, vaporwave took the initial political thrust of sampling and broadened it considerably: if sampling was at first an instrument of rebellion used by inner city black artists against white culture as an oppressive force, vaporwave then suggested the sample as an instrument of proletarian rebellion against the bourgeois. After all, the act of making and consuming vaporwave is inherently leftist in the way that any meme is inherently leftist: “open source,” decentralized and anarchic in nature, freely mutable and appropriable, and so on. I mean, to the extent that one could consider music to be a means of cultural “production,” the act of sampling existing music in the creation of one’s own is pretty literally a seizure of those means. Vaporwave also leveled aesthetic critiques toward capitalism, most notably in the appropriation of muzak, easily listening, city pop, and other “genres” of music so thoroughly sterile and commercial in nature that one has to wonder if they’d ever exist outside of a marketplace so demanding of homogeneity as ours. Daniel Lopatin himself actually brought that idea to the center of his work a year after releasing his first volume of Eccojams, dropping an incredibly seminal album built almost entirely around samples culled from the old TV commercials of the eighties.

Unfortunately, this highly interesting stuff is only one side of a sad story: sampling led an even weirder, cruder, arguably worse double life in the 2010s, basically because the capitalist machine saw money in the core intellectual project of vaporwave. Chuck Persons sez that by sampling music and teasing the absurdity out of it, anyone could be a musician; but that’s all predicated on a folk tradition that implies a kind of communal anonymity, no one taking anything too seriously, and so on. Capitalists envisioned a version of this that they could make money off of, for musicians who wanted to appear upright, wanted to seem technically capable, wanted to be stars — and those capitalists brought their vision into the world by creating a marketplace for readymade “samples” to be bought and commercially repackaged as original music. Speaking anecdotally, Splice is creepily prevalent in circles of music production that center around genres of music like hip hop and EDM; and I mean, to be fair, it’s highly seductive. The modern mind, or at least my mind, is instinctively attracted to puzzles, and piecing things together. It’s definitely easier than learning music theory or knowing yourself well enough to emotionally communicate through art. Businesses like Splice play right off of that instinct, telling you that creative genius is just a subscription fee away.

Of course, it’s easy to just blame the capitalists for this, but the line of thought that the Splice lizards work along isn’t necessarily a new or a unique one. In fact, I’d even say that it’s been a core aesthetic principle of pop music for at least as long as Kanye’s been famous: this is a guy who brings a million of the world’s most talented people into a room, puts them to work, and calls the end product his own — kind of just Splice IRL, if you think about it. It’s also the line of thought that I personally work along pretty often, and I think a lot of you folks might too, when you make playlists and mixtapes and identify them with a veil of authorial intent, even though it’s really just a collection of songs that you curated. This curatorial instinct, to constantly piece things together and tinker, is pretty much how directors of films get the sound, picture, writing acting, and post-production of their movies to project pure and total harmony; we call it auteur theory. I don’t think any of this is necessarily a bad thing.

But just as Martin Scorsese couldn’t make a movie without his massive team, I highly doubt many pop musicians could really make a good record off of the strength of their own skills anymore either. I don’t have anything to concretely connect the concepts, but I personally believe it’s why acts like Kanye have become so focused on becoming a whole different kind of celebrity, on the memes, on shock tactics — it’s pretty rare that any of the big faces have all that big of a role in making their music. Not that that’s anything new, I guess.

RILEY URBANO | KXSU Music Reporter