Author: Joel Dull

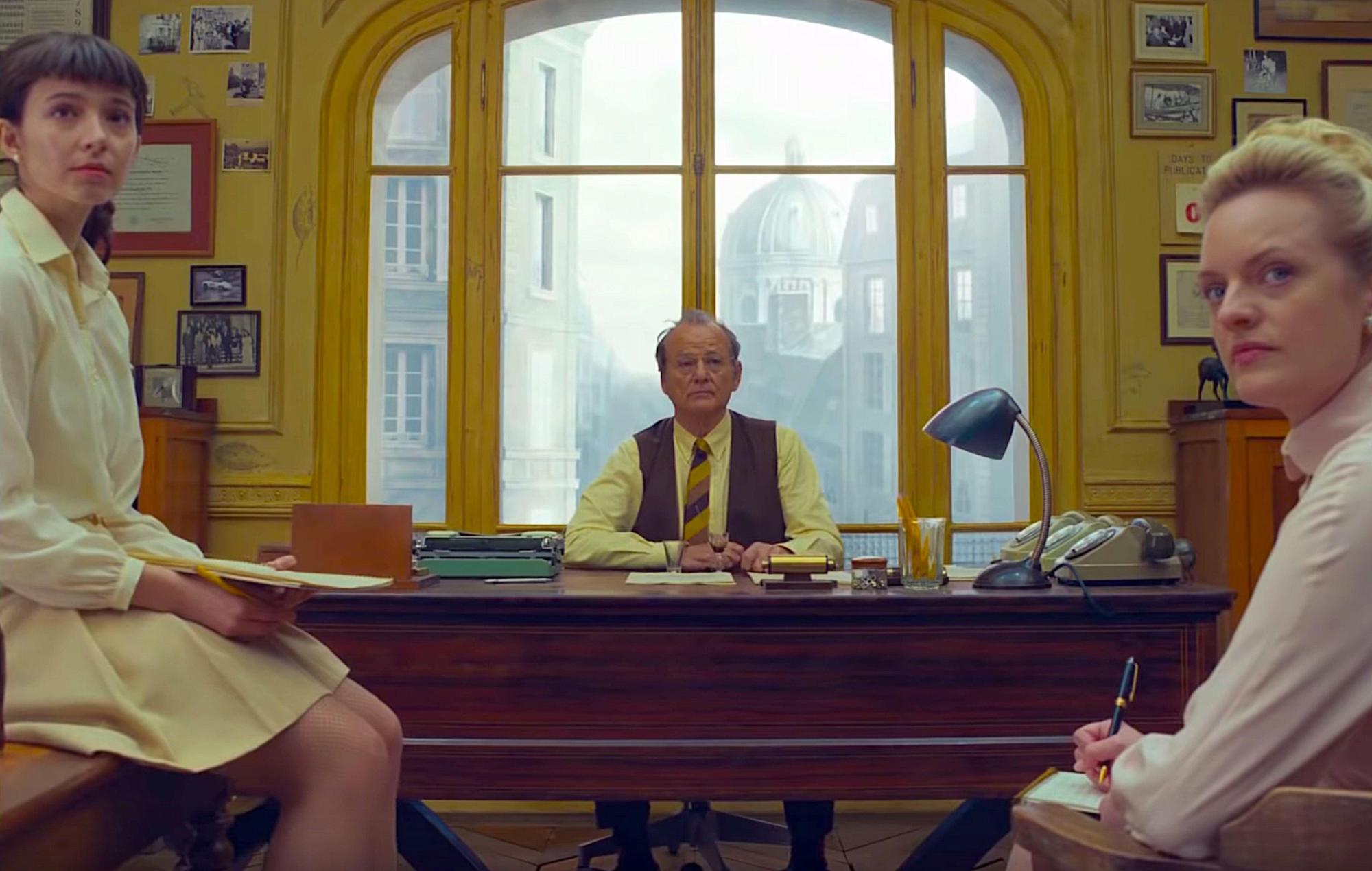

The French Dispatch is Wes Anderson at his most unintelligible and most poetic (not in a bad way).

Wes Anderson’s ode to journalism (in particular The New Yorker) might have you wishing your local theater came with a remote and a pause button. The fast-paced collection of vignettes that retell the best pieces of the fictional American newspaper “The French Dispatch” is a lot to take in. At times it feels like the story being told is a retelling by someone who skimmed the headlines and loglines of the Sunday paper.

Thankfully the enjoyment of this film doesn’t come from any attachment to the characters. Anderson is known for his storybook-like style, and in the French Dispatch, he transforms it into the pages of a newspaper. And it’s done to perfection. Headlines and New Yorker-esque illustrations separate each vignette. Voice Over from each of the fictional authors guide you through their stories as they remember it. Lines are snappy and often feel like loglines meant to pull you in.

The writers of “The French Dispatch” are eclectic. The film’s romantic view of journalism sees these writers as creative geniuses that should be left to their own devices and given the freedom to express themselves. Herbsaint Sazerac (Owen Wilson) looks as much like a Seattle hipster as he does a stereotypical Parisian. He would fit right in at the hottest natural wine bar of either city. J.K.L Berensen (Tilda Swinton) is the elegant art reporter that talks with every bit of snobbery imaginable yet remains genuine in her care for her journalistic subject. Then there’s Roebuck Wright (Jefferey Wright). Roebuck is a literary genius who remembers every word he’s ever written. His piece about policeman/chef Lt. Nescaffier (Steve Park) reveals that food is more than just food. It’s the events around the meal that hold true meaning.

The last of “The French Dispatch” writers is Lucinda Krements (Frances McDormand) is the intellectual political reporter for the paper. It’s her analysis of Zeffirelli’s (Timothée Chalamet) manifesto that simultaneously reviews Wes Anderson’s work in The French Dispatch. “It’s poetic (but not in a bad way),” is one of her last remarks on Zeffirelli’s work. Her analysis ironically summarizes the film itself. Throughout the film, Anderson favors a quippy, almost lyrical, flow to the dialogue rather than prose. The poetic nature of the script might detract from the clarity of the story, but it is part of what allows the individual characters to excel.

One of the brighter parts of the film is the noticeable shift in character voice from vignette to vignette. As each of the authors takes over, it not only feels like a new character is talking, it feels like a new writer is speaking. The newspaper framework moves it beyond good dialogue and writing. It causes Wes Anderson the screenwriter to disappear and allows the fictional journalists to take over. By creating distinct voices for each of the journalists, Anderson becomes an editor-in-chief using his visual style to put a cover on the paper and staple it all together.

The French Dispatch won’t have you crying or contemplating your ideology. Aside from a moment of extreme escalation by the Ennui police force, there is little in the film that will have you thinking of much at all. If The French Dispatch is a tribute to Wes Anderson’s inspirations, it exists in a canon of Anderson as a wonderful encapsulation of his aesthetic. Symmetrical and colorful, like flipping through the pages of a story book, or in some cases, the latest issue of The New Yorker.

Joel Dull | “Wow” — Owen Wilson | KXSU Arts Reporter